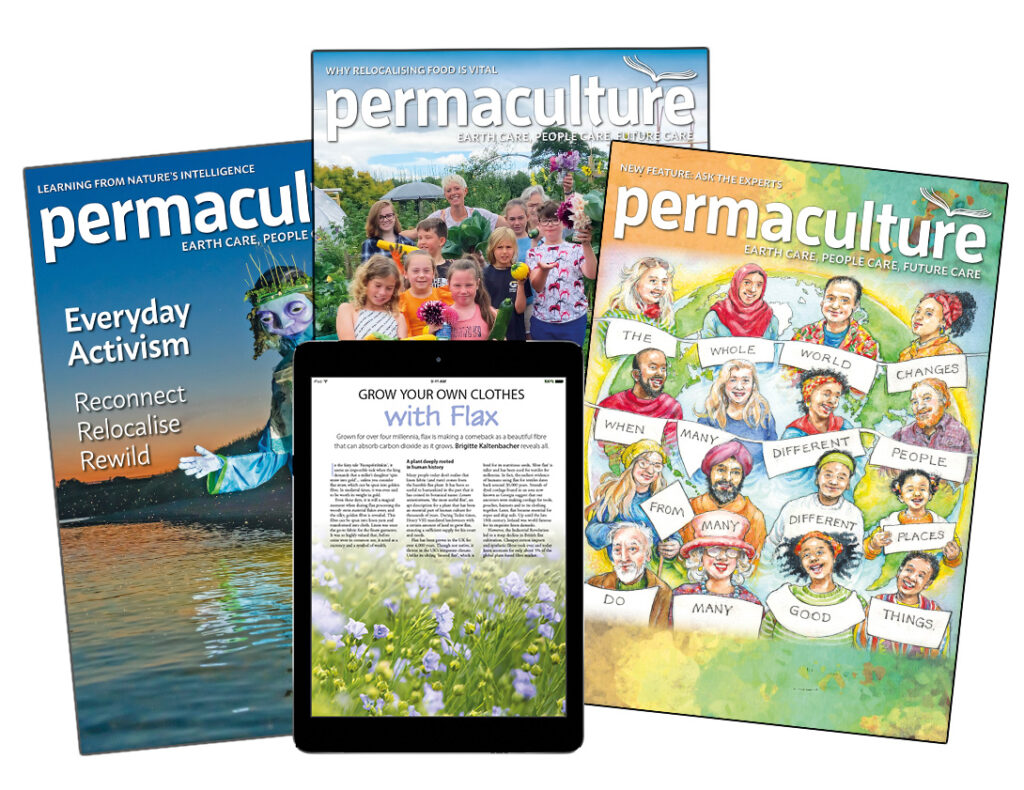

Permaculture

Wade Muggleton’s back garden, shown in the picture above, has been designed using permaculture principles. He collects rainwater, uses vertical space for growing food to get the most out of his garden and incorporates a wide range of plants and varieties.

The basic key principles of permaculture are probably the best place to begin to appreciate what it’s all about; it’s from those ethical principles that the twelve design practices are developed. It’s not just a way of gardening holistically with ecological sensibility, it’s a system of permanent cultures for sustainable living. There are just three principles, which are themselves common to so many philosophies and peoples over the world, but grounded in practicalities – and they seem to align quite closely with elements of allotment practice:

- Earth care

- People care

- Fair shares

Earth care

Care for the earth means observing and reducing the impact of our activities; a third of our ecological footprint derives from food, so of course it makes sense to grow as much as we can ourselves, which is the fundamental basis of allotmenting. At the same time we look to nurture and encourage a rich biodiversity above ground and below, to recognise webs of life and what can grow around us. So many of our sites are hugely valuable habitat with extensive tree and hedge margins, within urban settings.

Permaculture design uses nature’s own principles, of diversity, zones, complexity, layers and relationships among plants, humans and other creatures. Many allotments reflect that diversity – even if individual plots are sometimes regimented and bare, others are richly abundant, so that the mosaic of sites, and then the bigger picture of all our city wide sites together, make a valuable contribution to caring for the earth. Time was, allotmenteers used chemical fertilisers and pesticides and regularly burned their prunings; happily most have recognised the appalling damage those practices cause and YACIO tenancy agreements reflect that better.

People care

People care is basically about the power of community, which is so vividly present across and within our allotment sites. We have to get on with our neighbours – even when we disagree with their choice of cultivation practices! Most sites have generous informal systems of sharing: produce, knowledge, tools, time, seeds…..a gift exchange that sustains and forms bonds.

Our allotment movement has got better in recent years at responding to the different needs of different people, which is another expression of people care, asserting equity in the right to the benefits of growing your own food. We could do better still to establish caring relationships with our wider community, like growing for neighbourhoods, teaching skills and donating produce to food banks.

Fair shares

The history of the allotment movement in Britain is closely aligned with the idea of common people having a share of the wealth of land, after the Enclosures of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries took away access to local land for cultivation. The General Inclosure Act 1845 made rudimentary allotment provision for the ‘labouring poor’ mandatory – but it was not common land and remained part of the feudal hierarchy that still pertains in our county now. But a social movement gathered momentum and eventually (crazily concise summary this!) in 1922 the Allotment Act made provision available to all ‘where a need was shown to exist’. But there was never that sense of a right to ‘fair shares’ of access to land which characterises permaculture.

But we also need to recognise fair shares at the non local level. The industrial growth model is shaped to ensure some are winners and most are losers with no respect for the exploitation of people and the earth’s resources. So permaculture ethics invites us to look at our own consumption patterns in the broader context: what is the embodied energy involved in buying new tools, or new timber for some classy raised beds?

Our allotments can be a manifestation of these key ethical principles. A new year, a new resolution to live and grow more sustainably.

Views expressed in Plotlines are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of YACIO.